My Book for Amateur Photographers

Recently, I started reading heavily about photographic composition techniques in order to improve my photography skills. The more I read, the more I became interested in understanding how the brain processes scenes that it perceives in photographs, which lead me to look for answers in a nearly hundred-year-old theory.

This book is my attempt at summarizing what I learned and demonstrating how gestalt psychology can help amateur photographers compose better images by studying the quirks and biases of human visual perception, in particular by recognizing how the gestalt laws manifest themselves in interpreting visuals.

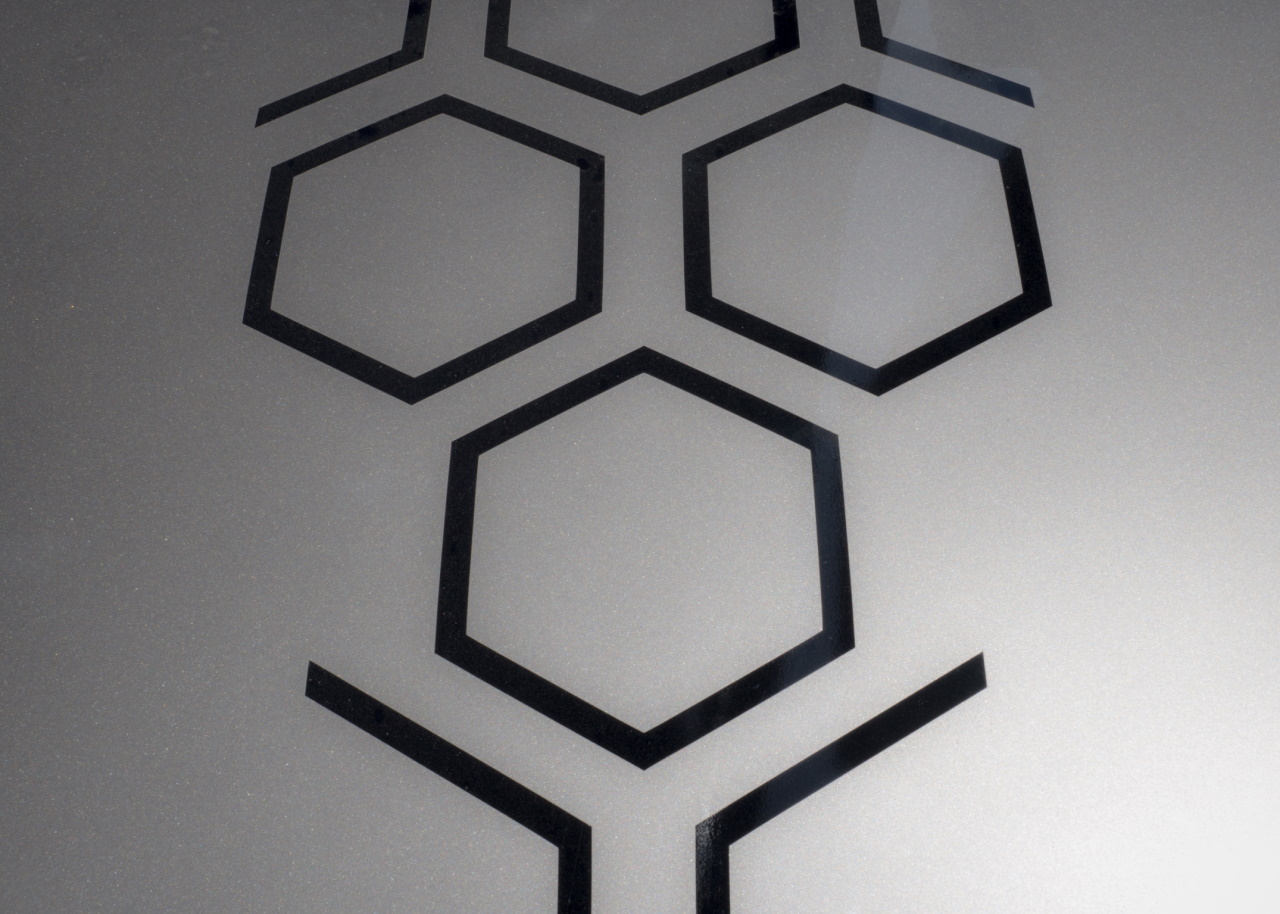

It was the study of optical illusions that led German scientists Max Wertheimer, Kurt Koffka, and Wolfgang Köhler in the first half of the 20th century to suggest that the structuralist approach prevalent at the time was not sufficient to explain human visual perception. They concluded that we don’t analyze individual elements of a scene and then combine them to make sense of what is there, but we perceive the totality before we become aware of its constituent parts.

This idea, that the whole is different than the sum of its parts, led to a new field of study called gestalt psychology which opened up the way to understanding the constructivist nature of the brain, making it possible to explain why we perceive a subjective and not an objective reality. Artists, designers, and advertisers soon discovered the importance of the principles that were formulated in the field of gestalt psychology for achieving aesthetically pleasing, minimalist designs that appeal to the subconscious mind.

In photography, the explicit use of gestalt psychology has not been prevalent. This may be due to the difficulty that most photographers, especially those doing mostly street photography, deal with instantaneous occurrences, where there is no time to intentionally arrange a scene as designers or advertisers can do. Nevertheless, understanding the gestalt principles of perceptual organization has the potential to provide significant insights into mastering photographic composition.

In an effort to exemplify the use of gestalt in photography, I provided here brief explanations for four concepts: emergence, reification, invariance, and multi-stability and twelve principles: meaningfulness, conciseness, good continuation, closure, figure/ground relationship, symmetry, common region, connectedness, proximity, similarity, common fate, and synchrony.

But obviously, the pointers I provided as to how they can be used in everyday practice of taking better photographs are neither comprehensive nor should they limit the reader’s creativity in any way. Every photographer must decide for herself which photographic composition rules to observe and how to use them to create the image she envisions.

It took me around two years to take the photographs in the book and yet they are far from sufficient or superior to do the topic any justice. Good photography often involves an element of luck to capture the perfect shot. This is not always possible in a limited time frame. I often preferred to set up my scenes and simplify them whenever I deemed necessary to explain the gestalt laws better, which was my main aim in writing this book.

While I didn’t necessarily intend to capture artistically exceptional photos here, I am looking forward to shooting more photographs with the gestalt principles in mind with the expectation of capturing frames excelling in sophistication and precision in the future. It is my sincere hope that this book will explain where rules of photographic composition have their roots and inspire other photographers to stand out with their art.

Most of us take it for granted that we all are equipped with an extremely powerful information processor – the best that evolution could come up with. The puzzling thing about the brain is though, that it accomplishes the most sophisticated tasks imaginable with a very simple trick: It matches patterns. But the brain is so good at this that it can make sense of incomplete, distorted, and even contradictory sensory information.

Indeed, we owe it to this capability of the brain, to the fact that it will seek and instantly detect structure, form, and organization wherever we direct our attention to, that we don’t perceive a chaotic manifestation of dissociated lines, curves, and shapes when we look around us, but meaningful objects. This allows us to rapidly scan our surroundings for elements that we require to accomplish our objectives without dedicating time and attentional resources to irrelevant or superfluous details.

On the other hand, the simplicity of the mechanism that the brain uses to create meaning makes us vulnerable to misconceptions. But the brain seems to subconsciously like looking at scenes where item perception occurs in accordance with the way its pattern matching mechanism works. This is one reason why I focus on the gestalt concepts in the first part of the book, so they may inspire us going forward. They often make it easier for us to understand the gestalt principles that form the core of the theory.

Having studied human perceptual organization, gestalt psychologists formulated a number of principles with the aim to capture its substance. Depending on the field of application, some of these are sometimes omitted or merged together, and sometimes used under different names. In this book, I present 12 principles as distinct rules. These should, however, not be thought of as laws, but rather as descriptive notions of how most of us deal with our perceptual experiences.

The brain’s main aim is to match what it sees to meaningful patterns it has stored in memory. The study of gestalt principles reveal that it attempts to do this by going from simple interpretations to more complex ones. For this purpose, it pursues an unconscious search strategy by following where different cues in the composition lead, supplementing missing information whenever it can. For the rest, it simplifies our visual field by grouping elements in the scene that appear to be related. This fast categorization is a very efficient way of merging perceptual information as we scan our environment based on clues it provides us.

Understanding human nature makes it possible to use the gestalt principles as tools for taking photographs that are engaging and at the same time appealing to the unconscious. An artist can structure her work according to a principle – positive sense – to appeal to specific perceptions, or intentionally go against it – negative sense – to highlight specific elements. Thus, there are three uses of the principles: An understanding of the human mind can help to choose a pleasing composition; the use in the positive sense can help to organize perception; and the use in the negative sense can help to highlight specific elements.